My Great Grandmother Had Four Last Names

Galician Genealogy

One of my retirement hobbies is researching and documenting my family’s history. Over the last several months I have spent hundreds of hours taking genealogy courses, listening to expert lectures, learning genealogical AI techniques, finding European archives, drilling into on-line databases, corresponding with other researchers, and squinting at 100-year-old documents written in Polish, German, Dutch or (heaven help me) Cyrillic. Then, I double that time organizing, annotating and writing all I have found into my genealogy software and computer files systems. Perla says that lately I spend more time in Galicia than in Toronto.

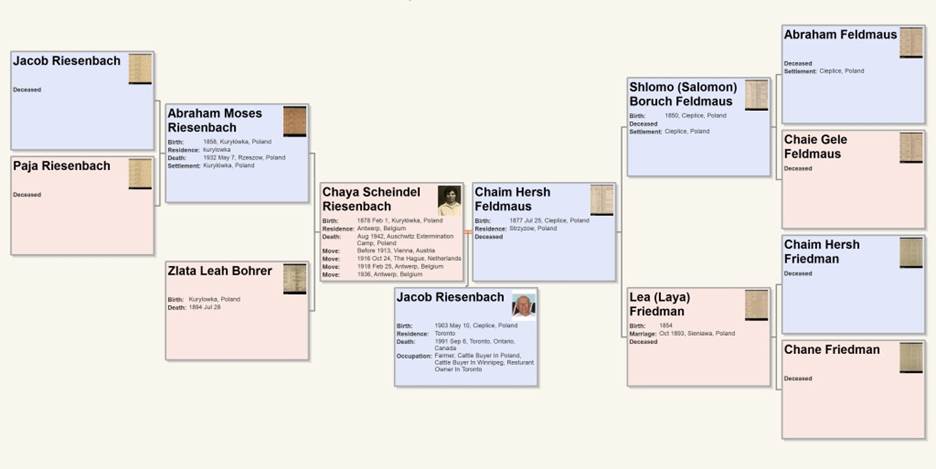

Working Backwards, Starting with Jacob

My focus these last months has been piecing together the backstory of my “Zaidy Yakel” (Jacob RIESENBACH). Jacob was my dad’s dad. Growing up in Winnipeg, I didn’t have the opportunity to spend a lot of time with my Zaidy Yakel who lived with my grandmother (“Bubby Eta”) in Toronto along with the rest of that side of my family. However, our families visited each other regularly enough through my childhood to let me establish somewhat of a connection with him. I came to know the basics of his life story, albeit without the deeper understanding that would come to me as an adult in later life.

Jacob was a Holocaust survivor who came to Canada from Poland when he was in his 40’s along with his immediate family (including my dad, Joe). Jacob arrived in Winnipeg in 1948 after spending a few years wandering post-war Europe and dwelling at a Displaced Persons (DP) camp in Austria. It was always with trepidation that I would broach the subject about his life in Poland. I was hesitant to ask him to recall those years of hiding, the fear, the loss, and the near-death experiences. In general, it wasn’t spoken of much during my childhood visits. But happily in later life, Jacob agreed to give several recorded interviews which I later digitized and that can be listened to on my YouTube Shoah playlist. The interviews largely focused on is experiences during and immediately after the war, so sadly, I still didn’t have a clear picture of his family life before the war.

Zaidy Yakel passed away in 1991 and so now the answers to my many questions require electronic detective work to uncover the people and events in his early life.

I thought I would first focus on researching Jacob’s mother …..

A Galician Birth

Jacob was born May 10, 1903, in the village of Cieplice in southeastern Poland, about 90km west of what is now the Ukrainian border. At the time of his birth, Cieplice was part of Galicia and was under the control of the Austro-Hungarian empire. More than a million Jews lived in the broader territories of the empire, but most of them lived in Galicia. In many towns Jews accounted for a large proportion of the population. For example, according to the census of 1910, Jews accounted for 30% of the 55,000 residents of Przemyśl (a nearby city).

Sadly, Jews across Galicia were a suppressed underclass, despite emperor Franz Josef emancipation of the Jews some 35 years before Jacob was born. Jewish marriages and births were commonly seen as illegitimate because they didn’t happen under the auspices of the Catholic church. From the perspective of the Polish authorities virtually all Jewish babies were born “bastards” and all Jewish couples lived together in sin. To legitimize a marriage or a birth, Jews were required to go to a government office and formally register. This not only cost money (Jews were charged especially heavy fees for this privilege), but it also informed the government as to their whereabouts and family situation. This administrative data could be problematic down-the-road as it gave the authorities the knowledge to impose special taxes, conscript young men into the army or to control the growth of Jewish population centres. Thus, civil registration of Jewish births and marriages weren’t always done. Sometimes they were done years after the fact only when such things as passports or legal documents were needed.

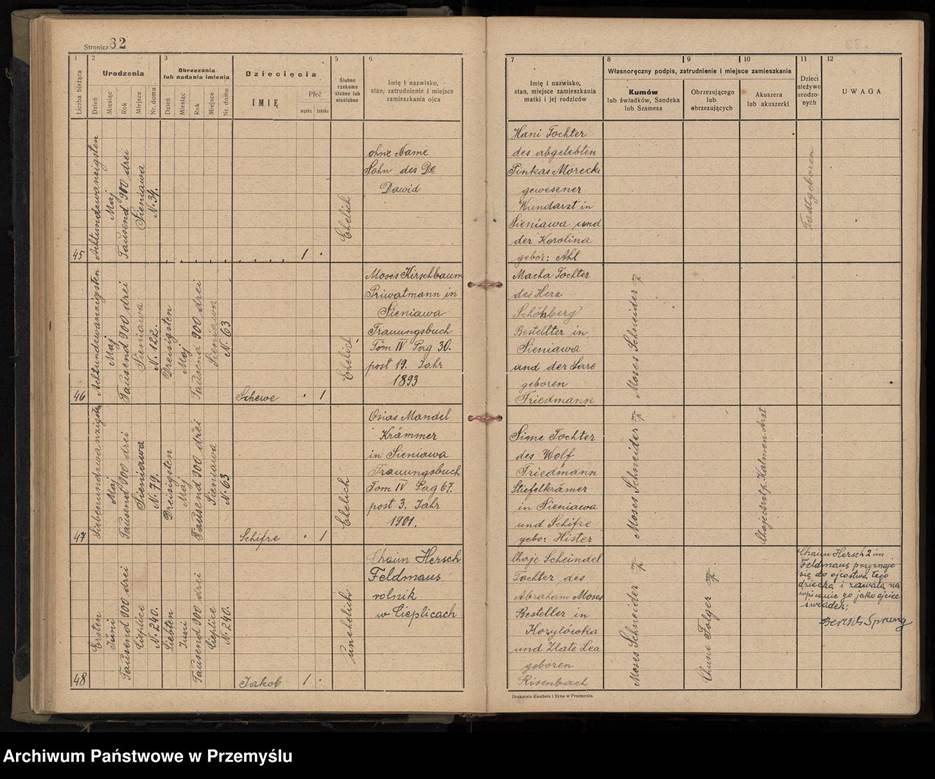

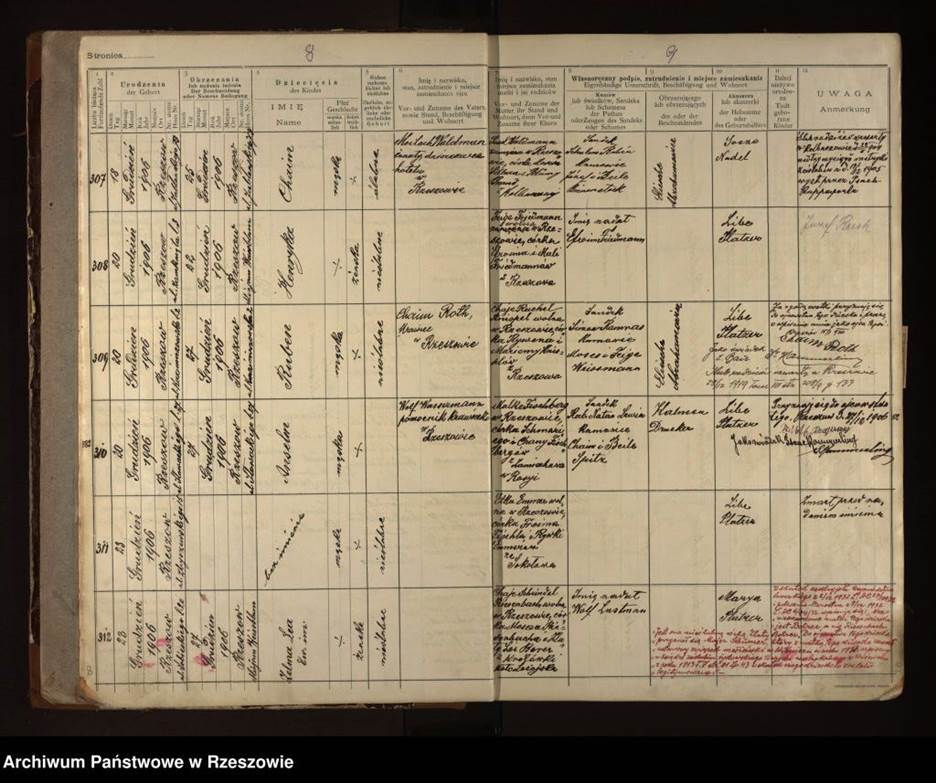

Drawing on the valuable archiving work of several organizations that preserve Jewish history, I was able to find Jacob’s birth record. The picture below is a digital image of a Galician birth ledger. The entry recording Jacob’s birth is the last of the four rows on this double-page. The entry is hand written in German — the language most commonly used for government and business transaction at the time. The entry records his mother’s name as Chaya Scheindel and his father’s as Chaim Hersch. As for his parent’s surnames, here is where things get complicated. There is an annotation in the right hand side of his birth record, in the column labeled ‘Attention’. The text says “Chaim Hersch Feldmaus acknowledges his paternity of the child. He consents to the child being adopted and recognized as his offspring“. Signed by a witness, Berisch Sprung.

There is much that is noteworthy here. First, the annotation is written in Polish and is in a different handwriting than that of the rest of the text. While it is not possible to be sure, the language and the tone of the annotation implies that the note was written into the ledger some time after the birth was recorded. And most notably, the annotation raises a mysterious question regarding the marital status of my great grandmother and great grandfather!

.

Maternity and Paternity in 19th Century Galicia

Through conversations and recorded interviews with Jacob, I came to understand that that there were mysteries surround his upbringing. There was the unexplained departure of his biological mother (Chaya Scheindel) from the family home about a year or two after he was born. This fact was well known in my family but not spoken of too frequently given the sensitivities. I didn’t know why Chaya Scheindel left and I don’t know to this day. The recordings that I have of Jacob might contain some further hints of why his mother left, but it will take careful listening to the “Yidlish” he spoke to tease out any further facts that might have been overlooked in my early listening. As they say in academia, this is a topic for future research.

But, what was going on here with this birth record annotation? There could be a number of explanations to this cryptic note. The simplest interpretation is that Chaim Hersch and Chaya Scheindel were previously married in a Jewish ceremony, and this note merely documents that Chaim Hersch later dutifully registered Jacob’s birth with the authorities. Another interpretation is that baby Jacob was conceived by the couple out of wedlock and that Chaim Hersch and Chaya Scheindel are legally adopting him into their family now that they were formally married. Yet another interpretation could be that Chaim Hersch and Chaya Scheindel were never married, but that Jacob was indeed their biological son. A final (and somewhat uncomfortable) interpretation of this note could be that Chaim Hersch was not Jacob’s biological father. Some other man was. For some reason Chaim Hersch felt the need to legitimize the child’s legal status by legally adopting him. In this interpretation, Chaim Hersch is bringing Jacob into his home as a son, even though he is not the father. Without DNA testing, we may never know which of these is true.

Naming in 19th Century Galicia

What surname should baby Jacob have? In Galicia the time, a doctrine that was shared between the Austro-Hungarian authorities and rabbinic tradition was that the mother was the only certain parent of a baby. Thus, it was the default position that babies were documented in legal records with their mother’s last name. Later, if a father registered the child with the authorities and paid the fee, the child would be known by the father’s surname. However, this policy merely kicked the proverbial can down the road. If a child is to be assigned his mother’s last name, then what is the last name of the mother? Was the mother’s last name the surname of her father or the surname of her mother? The answer is sometimes one, sometimes the other. Frequently, both were used at different times and in different situations.

By the way, this recurring issue of ambiguous surnames is a frustrating problem for doing genealogical research. Some focus can be had by also levering the first names of a baby’s parents and the town they come from. However, given the Jewish tradition of naming a baby after a deceased relative, you could find multiple people with the same first name and same last names from the same town but born at different times!

Bohrer, Riesenbach or Feldmaus?

So, that brings us to Jacob’s mother, Chaya Scheindel. Chaya Scheindel was born in Kuryłówka, Poland, in 1878. Kuryłówka is a rural area located just to the northeast of the city of Leżajsk.

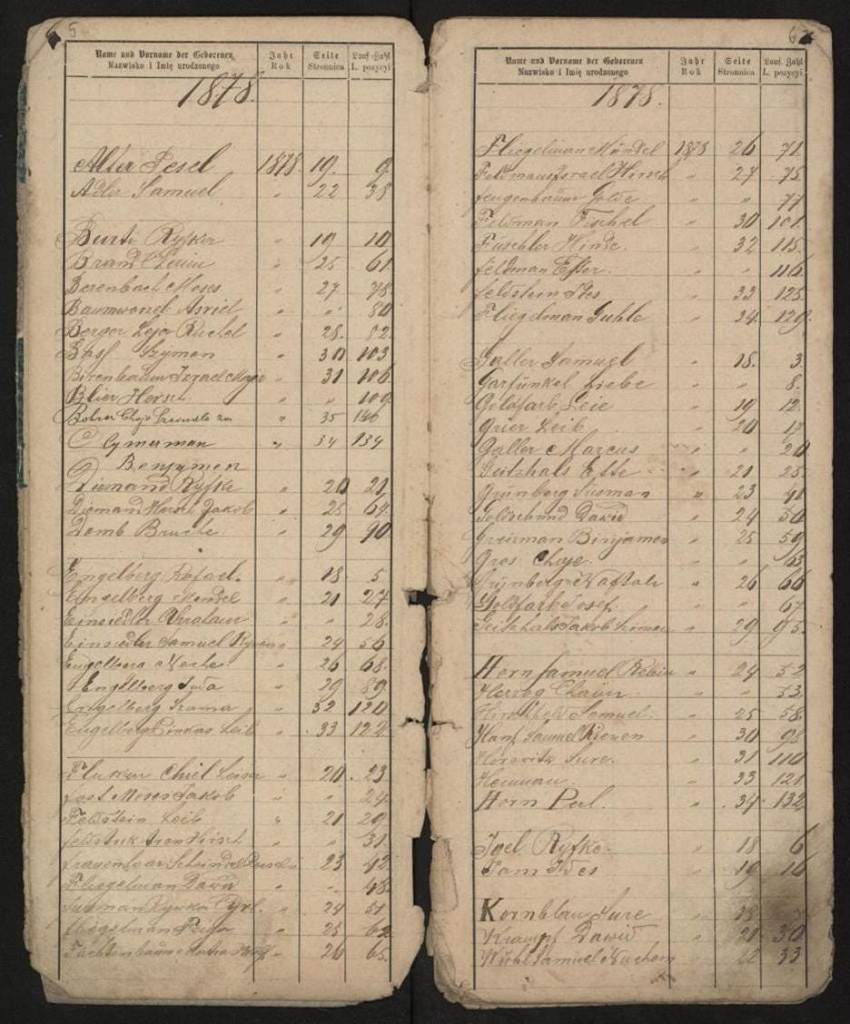

The picture above is digital image of a nearly 150 year-old ledger recording my great grandmother’s name: Boher Chaya Szendle. This ledger book is an index; it lists the names of the Jewish children born in a particular region and particular year along with a reference to a page on a separate ledger book where the full record of the birth can be found. This full record would contain additional administrative and family details as shown in Jacob’s birth record above.

Organizations such as JewishGen, Gesher Galicia and JRI-Poland have undertaken multi-year projects where trained experts digitize historical records such as these. Moreover, they translate and organize the information so that researchers (such as me) can search for names of individuals or towns in their databases which reference the original digitized documents. Their work is invaluable – without it, the only way to gather this kind of information would be to physically visit each and every archive with an interpreter by your side.

Many thousands of ledgers such as this one have been digitized by these Jewish historical organizations. However, there are many thousands more that exist in dusty cabinets in municipal offices and national archives have not been digitized and/or published. Over the years and over the wars many historical ledgers have become lost despite preservation efforts. Sometimes, a detailed birth ledger has been lost and only it’s birth index ledger exists. This may be the case for the full birth record of Chaya Scheindel. To date, I have not been able to find the full record of Chaya Scheindel’s birth; just this index ledger referring to it. However, through other means, I have been able to piece together a few facts about Chaya Scheindel’s and her parents.

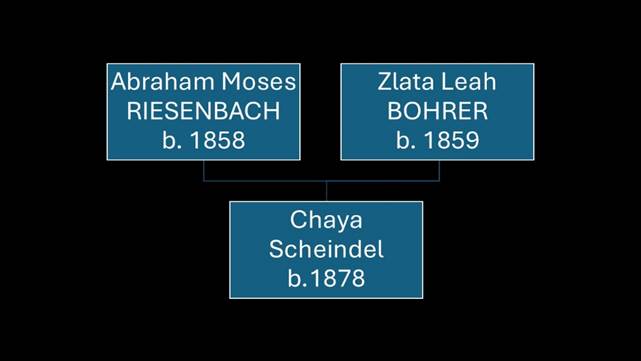

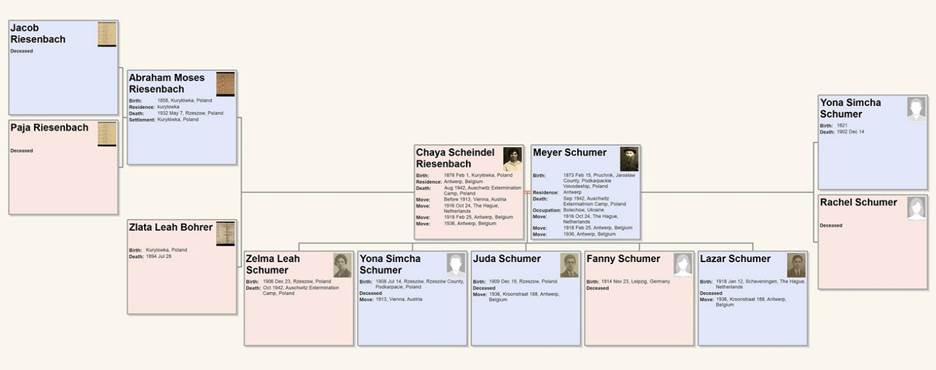

Chaya Scheindel’s father was named Abraham Moses RIESENBACH and her mother was Zlata Leah BOHRER. Abraham Moses was born in 1858 and was a businessman (according to his death record that I have in my files). He lived in Kuryłówka and died in 1932 at the age of 74. Zlata was born in 1859 in Kuryłówka and died in Rzeszow in 1894 at the young age of 35.

Abraham Moses and Zlata Leah had three children together before she passed away. Besides my great grandmother Chaya Scheindel (b. 1878), they had David (b. 1887), and Sara (b. 1891). I have reasonable confidence that Sara as indeed Zlata and Moses’s daughter, but I am not completely confident that David was indeed their son. My conclusion is based on circumstantial evidence that I’m hoping will be confirmed through information from a German archive that I have requested and am waiting for.

In any event, Chaya Scheindel gave birth to her son Jacob in Cieplice in May of 1903 (a mere 20km away from her own birthplace). Chaim Hersch FELDMAUS claimed paternity for the boy and I presume (perhaps naively) that they lived together as a family for a time in the nearby town of Sieniawa, Poland.

In my collection of documents, I have records listing Chaya Scheindel has having the last name BOHRER and other documents where she is listed with the last name RIESENBACH (and other document where she has yet another last name — stand by). I have not found records where her surname was recorded as FELDMAUS. That could mean that no such document exists, or it could mean that I haven’t found the right document yet, or it could mean that she and Chaim Hersch were never formally married according to the local civil authorities. But it is conceivable that at some time in her life up to 1903 she went by one or more of those three surnames.

Also of note is that Jacob, my grandfather, took the name of RIESENBACH as his surname. On more than one occasion he was recorded as saying that “it was my mother’s name”. I have records where officials documented his surname (and those of his wife and children) as FELDMAUS, but he never used that name himself.

A New Husband and A New Last Name

For reasons that are not clear, Chaya Scheindel left her son Jacob Riesenbach (and notionally, the father of her child, Chaim Hersch) within 3 years of Jacob’s birth. My research places her departure sometime between mid-1903 and mid-1906.

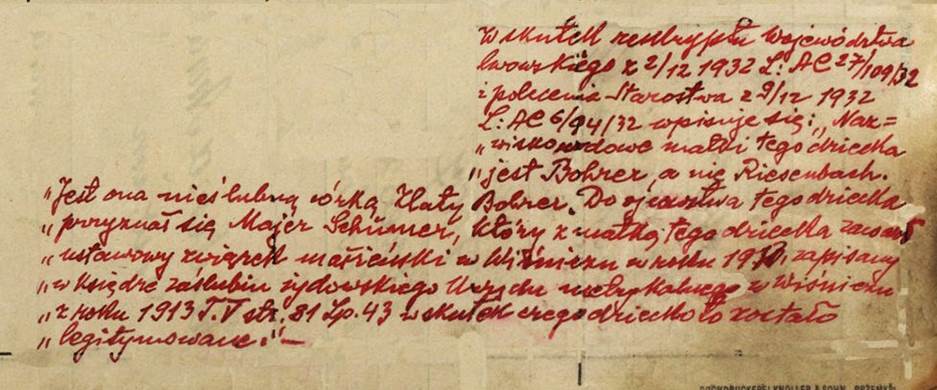

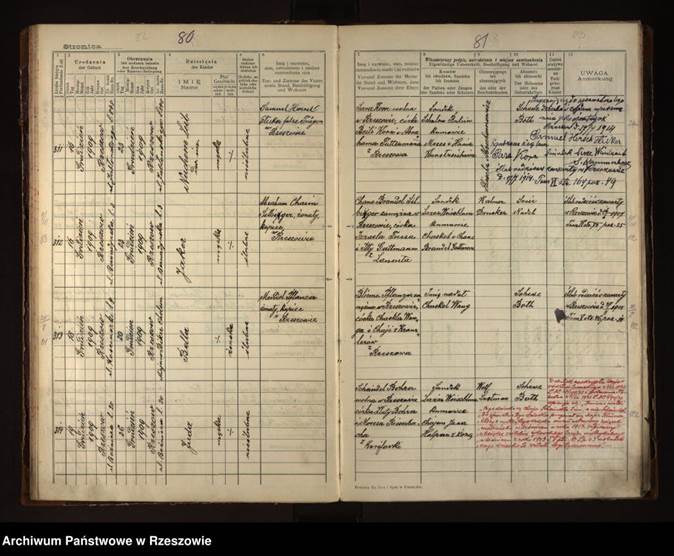

The next chronological record I have that refers to Chaya Scheindel is from the city of Rzeszów, 60km from Sieniawa . The digital image below is a page from a Jewish birth ledger which lists her as the mother of the girl Zelma Leah. Zelma Leah was born December 23, 1906. The German handwriting in the column for the mother of the baby reads: Chaje Scheindel Riesenbach from Rzeszow, daughter of Moses Riesenbach and Zlata Lei Borer from <Krolowski?>, near Lesajsk.

Mysteriously, the column for the father’s name, occupation and place of residence is blank. However, there is a fascinating annotation in red ink in the “Attention” column of the birth record. Thanks to help from a “View Mate” volunteer from JewishGen.org, I was able to have it translated.

The red text (expanded above) was written in Polish some time after the birth of Zelma Leah. It is an official directive from the Lwow Voivodeship and the Starostwo district office. It asserts that Chaya Scheindel RIESENBACH, the mother of the child’s surname is BOHRER, daughter of Zlaty BOHRER. Further it mentions Majer SCHUMER who “przyznal sie” — confessed or admitted to paternity of the child. The text refers to the file number of a particular Jewish marriage registry from 1913. The text concludes by asserting that the child’s legal status is thus legitimized.

When I first saw this document, I was flabbergasted. My great grandmother had a child with another man so soon after leaving her first husband! With this birth record, I had hard evidence that after leaving her first-born son and home in Sieniawa, Chaya Scheindel went to live in or near Rzeszow. In 1906 she got pregnant and had a child the same year.

Adding to this new chapter of her life, I have found two other records from this period mentioning Chaya Scheindel. Both are birth records. Her son Yona Symcha was born on July 14, 1908 and another son Juda was born on December 19, 1909. Both of their birth records have the same bold annotation in red ink. Both assert that Majer (spelt Meir or Meyer in other documents) SCHUMER married Chaya Scheindel in 1913 and has claimed paternity over the children, thus legitimizing them.

Thus far, I have not located a copy of the marriage record of Chaya Scheindel and Meyer SCHUMER. However, these birth documents and a few other documents in my collection make reference to their civil marriage in Rzeszow in 1913.

Being Jewish In the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1880 – 1913)

Many of the records I have of my ancestors list them as businessmen, tradespeople, farmers, furriers, inn operators and the like. They were not wealthy people – they worked as farmers and in the trades scratching out a living the best they could. Most of their Jewish neighbors were in the same socio-economic strata. Galicia was one of the poorest regions in the empire, and the Jewish population was made to suffer more than most through economic marginalization, restrictions on land ownership and limited entry into modern professions. Antisemitism was (and sadly still is) a potent force in European politics and civil society. Elites and large segments of the peasantry blamed Jews for their economic hardship, particularly in rural areas where occupations were limited and Jewish merchants and moneylenders were prominent. Nationalist political parties frequently used antisemitic rhetoric to rally popular support and to push for policies favoring Polish Catholics in local administrations, schools, and cooperatives.

As poverty increased, hundreds of thousands of Jews emigrated from Galicia during these years. Among those packing up their belongings and seeking a better life elsewhere were Chaya Scheindel and Meyer SCHUMER.

The Hague, Netherlands (~1913 – ~1920)

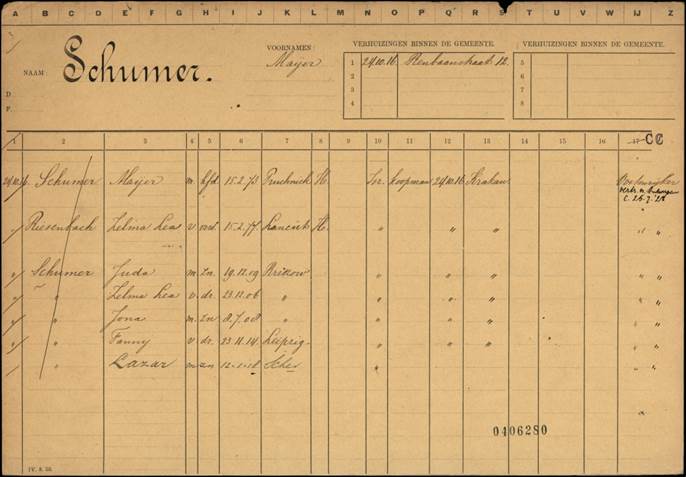

The next document I have uncovered that records events in my great grandmother life is from the city of The Hague, Netherlands. It is called a “Household Card” (shown above) and it records the inhabitants of every domestic residence in the city. This document revealed a lot of important information about her new life. First is the fact that after their marriage in Rzeszow in 1913, Chaya Scheindel, Meyer and their children moved 1,500 kilometers west to take up residence in the Netherlands. Next is that this document records two more children (that I assume are the natural born children of the couple). Fanny (b. November 11, 1914) and Lazar (b. January 12, 1918).

Dealing first with Lazar, his birthplace is recorded as “Schev” which is an abbreviation that likely stands for Scheveningen, a suburb of The Hague. But more noteworthy is the birthplace of Fanny, recorded as “Liepzig”. Liepzig, Germany lies about half-way on a direct line between Rzeszow, Poland and The Hague, Netherlands. The Netherland archive that has digitized this card claims it is from a 1913 collection. However, it appears that information on the card was added in later years. For example, the entry for Lazar appears to have been written with a different pen. If this is correct, Fanny would most likely have been born on the journey from Poland to the Netherlands.

Also note that Chaya Scheindel RIESENBACH’s entry on the card has numerous mistakes. Her first name is erroneously recorded as Zelma Lea (her daughter’s name). Her birth date and birthplace are also incorrectly recorded.

There is a box in the upper part of the card labeled (in Dutch) ‘Movements Within The Municipality”. In this box there is a date (October 24, 1916) and the address Renbaanstraat 12. Using Google Maps, I looked up this address and found what might have been the SCHUMER-RIESENBACH home in The Hague:

With this more complete information, I can now draw the family tree of my great grandmother’s second family:

Finally, there is an intriguing annotation in Dutch on the right-hand side of the card that says Vostenrijker vertr. n. Antwerpen which translates to “Austrian moved to Antwerp about July 25, 1928”. It would not be unusual for the immigrant SCHUMER-RIESENBACHs to be referred to as Austrians, given that Galicia was part of the Austro-Hungarian empire up to World War I. However, the note raises another contradiction. It asserts that the they left The Hague in 1928. That date is much later than the next piece of information I have on my great grandmother’s life journey.

Antwerp, Belgium (~1920 – 1942)

In 1920 the SCHUMER-RIESENBACH family received passports from the office of the counsel general of Holland and prepared to leave for Antwerp, Belgium. They arrived in Antwerp and initially settled in an apartment at Breughelstraat 35. Some time passed in which I have no information about the family or their activities. In 1936 The SCHUMER-RIESENBACHs requested a permit that would enable them to settle permanently in Antwerp. This request triggered a police investigation and report. My search of the Belgium historical archive turned up this detailed police report which can be examined below.

The dossier consists of a half-dozen typewritten pages. The triggering document is Dated December 9, 1936 from the office of the Minister of Public Safety to the office of the Police. It requests an report on the “… conduct, morality, social interaction, actual means of subsistence, activities and behaviour” of the two SCHUMER boys Lazar and Juda. The resulting report details their employment as apprentice diamond cutters working for Zelma Leah’s husband (their brother-in-law), Szymon REINHOLD. Szymon (or Simon or Shimon in Yiddish) often went by another surname FUHRER. He was born November 27, 1906 in Ciężkowiczk, Poland . According to the report, Szymon was a diamond cutter residing at Plantin en Moretuslei 14.

The report found that the two boys worked long hours, were paid on commission, and had a good reputation. Apparently, their earnings provide for their mother, as their father (Meyer), a former shopkeeper, was unable to work or obtain employment. The document also updates their address in Antwerp to Kroonstraat 188.

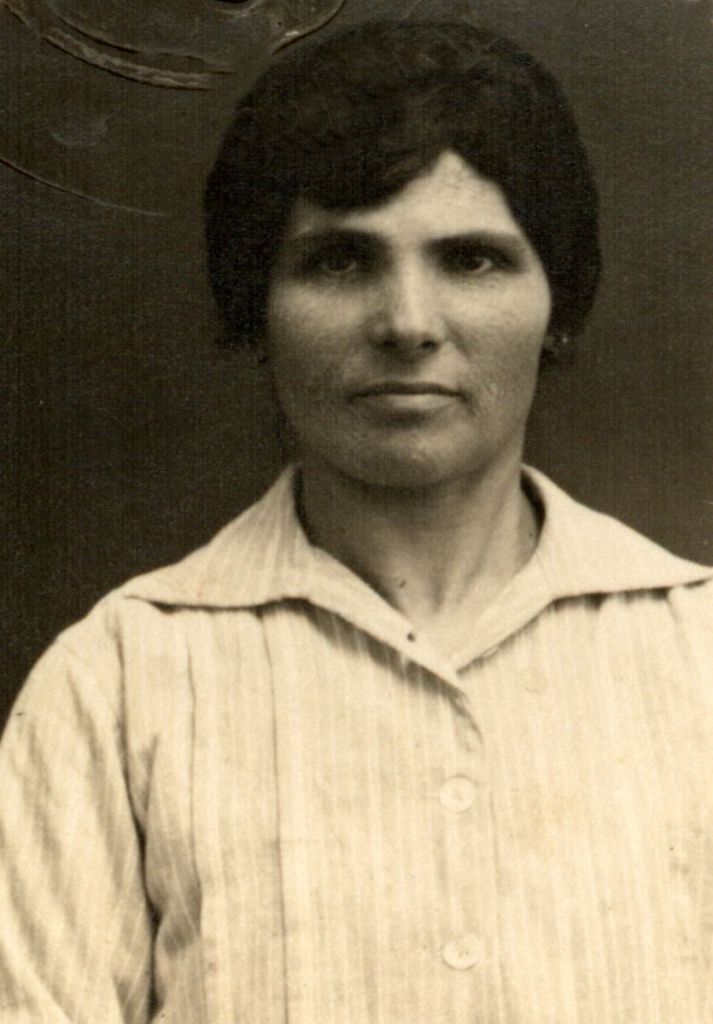

But to my mind, the most exciting find in this dossier are photos of my great grandmother, her husband Mayer, and three of their children! These photos bring to life the actual individuals who were my extended family, rather than merely a collection of names, places and dates.

I do not know the whereabouts of Yona Simcha or of Fanny SCHUMER during this time. There was a note in Yona Simcha’s birth record asserting that he was raised by a SCHUMER grandmother while Yona Simcha’s mother (Chaya Scheindel) was away in Vienna. I have not yet turned up any information supporting the claim that Chaya Scheindel traveled to Vienna. This is yet another stream of inquiry that I’ll need to undertake in the future.

Zelma Leah married Szymon REINHOLD (date as yet unknown) and, in 1937, she gave birth to a son Jacques Henry and, in 1940, to a daughter Paula. Even though times were hard in 1930’s Belgium, these grandchildren must have brought great joy to my great grandmother.

Being Jewish in Antwerp in the 1930s

In the 1930s, Belgium’s Jewish community numbered around 70,000, many of them recent immigrants from Eastern Europe. They faced mounting challenges stemming from both the depression and the rise of fascism in Europe. The Great Depression struck Belgium hard, causing widespread unemployment and hardship, particularly for immigrant Jews who were often concentrated in trades like tailoring, peddling, and diamond cutting. The diamond industry, a significant employer of Jews, suffered during the depression. There were efforts by local authorities to “cleanse” the trade of unlicensed or foreign workers and these efforts inevitably targeted Jews. As the economy worsened, Jews were increasingly scapegoated as competitors for scarce jobs.

The Belgian government implemented restrictive immigration policies in the early 1930s, responding to domestic pressures and rising xenophobia. While Belgium did not enact antisemitic legislation similar to Germany’s Nuremberg Laws, Jews faced all kinds of bureaucratic obstacles to employment and residence permits. The late 1930s were a precarious period for Jews in Belgium. But far worse was to come under the Nazi occupation which began in 1940.

A Tragic End

I know virtually nothing more of Chaya Scheindel’s time in Antwerp beyond this 1936 police report. When the war finally came to Antwerp things must have turned very grim for my great grandmother and her family.

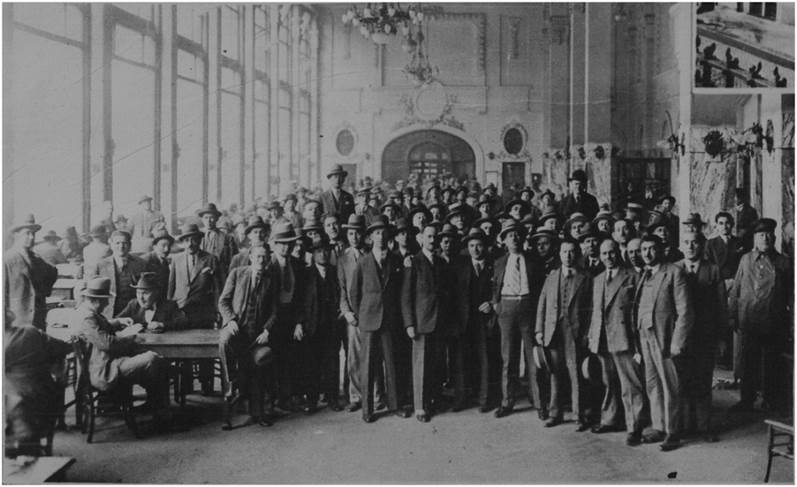

Beginning in 1942, Jews were systematically rounded up by German forces with active collaboration from the Belgian police. The police records gathered from their 1936 request for permanent residency must have helped the authorities locate and arrest the SCHUMER-RIESENBACH family. The main site of internment and deportation of Jews and other undesirables was the Kaserne Dossin barracks in Mechelen, located half way between Antwerp and Brussels. Over 25,000 Jews were held there before being deported by train to Auschwitz and other extermination camps. Historical documents record that prisoners suffered harsh conditions, minimal food, and cruel treatment inside the camp.

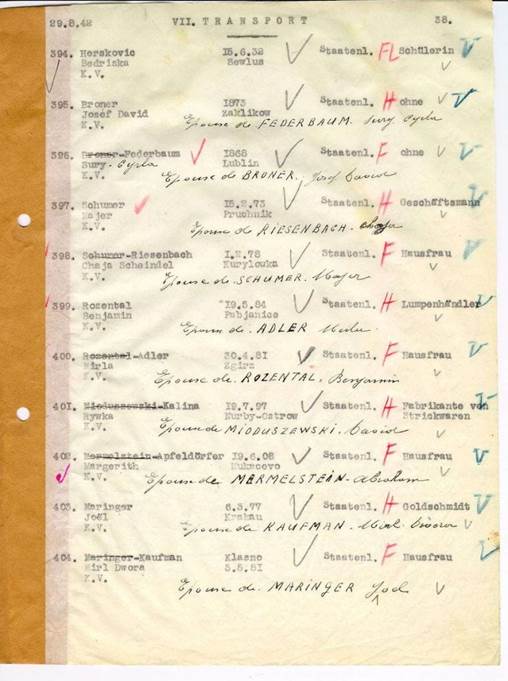

I have located documents from the Belgium archives (including the one above) that provide sad proof that Chaya Scheindel and Meyer were indeed interred at the Kaserne Dossin prison Camp. From there, they were deported by train on Transport VII. The transport left Belgium in September of 1942. The transport arrived in Auschwitz Birkenau and it is here that the story of my great grandmother comes to a tragic end.

Did Anyone Survive?

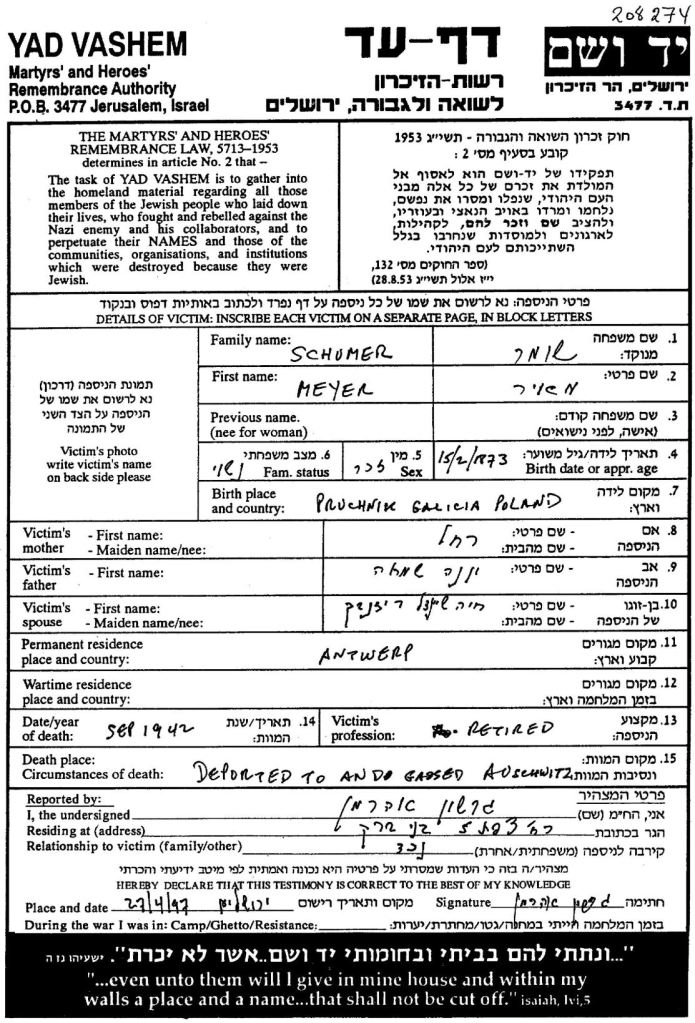

Documents at Yad Vashem detail that Zelma Lea, her husband and children were also murdered . But, I have reason to believe that some of Chaya Scheindel and Meyer’s children survived the Holocaust.

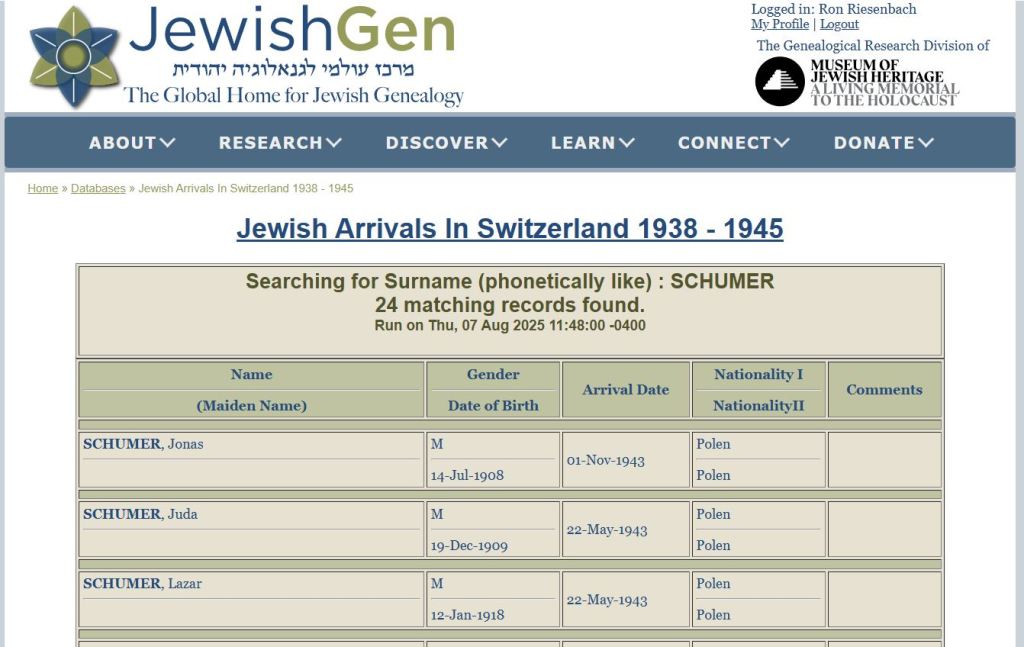

JewishGen has a database of Jewish Arrivals in Switzerland. Running a search on this database I came across three intriguing names: Jona (Yona?), Juda and Lazar SCHUMER. If these are indeed Chaya Scheindel’s children, then they may have gone one to build families of their own and left descendants. I did reach out to a person I found on MyHeritage.com that had one of these SCHUMER boys in her family tree. I asked her if we could share information about them. Unfortunately, she declined my request. I will keep trying.

Also fueling my hope is a discovery, through MyHeritage.com and BillionGraves.com, a grave in Kiryat Shaul Cemetery, Israel with the inscription (translated from Hebrew) Yehuda Schumer, son of Meir and Chava Scheindel, Died 9 Shvat 5749 (corresponding to January 15, 1989). If this is the same person as Chaya Scheindel’s son, then at least one of her children with Meir SCHUMER survived the war and settled in Israel. Juda may have left descendants if he started a family after emerging from the Shoah.

Also intriguing is that a man by the name Aharon GERSHON completed a Yad Vashem testimony form in 1997. At the bottom of the form, near the signature line, he states that he is the grandson of Meyer SCHUMER. It could be that he is the child of one of Chaya Scheindel’s children. However, note that Chaya Scheindel was Meyer’s second wife. He did have children with his first wife and thus Aharon GERSHON may have been from this other branch of his family. I will need to investigate further.

Through these and other leads, I have hope that there are survivors of Meir and Chaya Scheindel’s line who have found a safe home and have built families themselves. I hope in the coming months and year to find these descendants through my ongoing genealogy research. If there are survivors from her line, then I have cousins somewhere in the world that may be able to shed more light on the life story of our great grandmother, Chaya Scheindel; the woman with four last names.

Acknowledgment

Preserving Jewish history is a team effort. Many Jewish organizations have been formed and many volunteers invest their time and their effort to ensure that our rich heritage is safeguarded as a legacy for future generations. I am very thankful to the Jewish organizations and volunteers whose labours preserve the documents that photographs that I used in this story and will use in the stories to come. Even the commercial companies who profit from people like me deserve praise.

Beyond my own family documents, audio tapes and video tapes, I levered the sources and expert knowledge of the following organizations and individuals that I wish to acknowledge:

- JewishGen (especially Educator Barbara Rice and “View Mate” volunteers Lev Newhall, Denise Fletcher)

- Gesher Galicia

- JRI-Poland

- Yad Vashem

- Antwerp Archives

- German Federal Archives

- Polish National Archives

- Wiener Stadt und Landesarchiv

- Markowa Ulma-Family Museum of Poles Who Saved Jews in World War II

- For profits: MyHeritage.com, Ancestry.com, Geni.com, FamilyTreeDNA.com, Billion Graves