Account of a Return to Poland

Written by Gabriel Anmuth, July 2025

Translated to English and adapted by Ron Riesenbach, August 2025

We returned because here, over a thousand years, one of the richest and largest Jewish communal lives in the world was built: communities, synagogues, study, markets, families, culture. All that fabric was wiped out in just a few years by the Shoah.

And yet, as you walk through villages, forests, and synagogues, that millennial continuity becomes present. It becomes present there. Right there.

With that spirit we undertook this trip together with my wife, Marisa Kahan, and my (now adult) children, Tami and Ariel: a return to our roots and to the memory of our people.

Warsaw – POLIN Museum

Illustration 1: Monument to the Heroes of the Ghetto Illustration 2: POLIN Museum, Warsaw

On the first day we stayed in Warsaw to visit the POLIN Museum (its name means “Poland” in Hebrew). It is a state museum that recovers and makes visible the thousand-year history of Judaism in Poland, a history that culminates in the Shoah with the near-total destruction of the Polish Jewish community. In 1939 there were more than 3,000,000 Jews in the country; today, barely about 5,000.

The museum is modern and educational, with an updated, reflective historical narrative that does not conceal hard truths. It was an excellent educational prologue to our trip: a macro view before focusing on the region of Galicia, Subcarpathia, with Rzeszów as the main city and Łańcut as the seat of the district where my grandfather was born.

My grandfather, Samuel Anmuth, is considered a Łańcut Jew even though he was born in Markowa, a small village that belonged to that district.

Markowa – The Legacy of the Righteous

We stayed three days in Rzeszów, from where we set out to visit Markowa (25 km away) and Łańcut (19 km away).

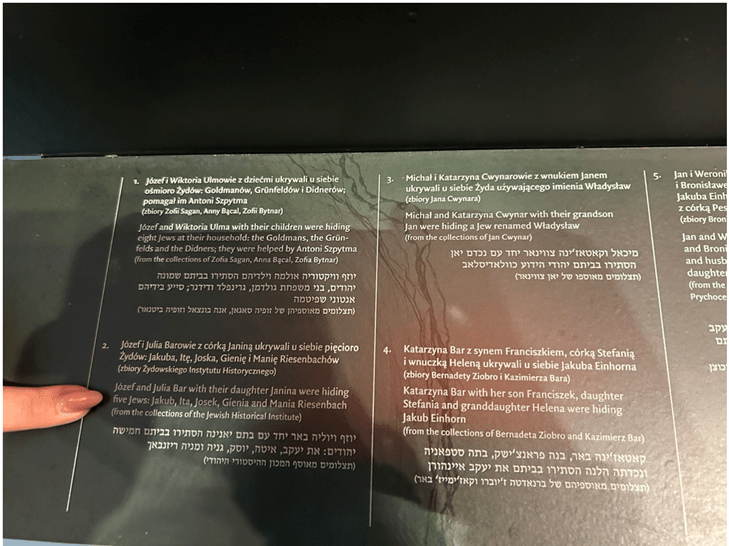

It is worth noting that about 120 Jews lived in Markowa before the war. There were nine families there who hid and saved Jews. One of those families was that of Józef, Julia, and their daughter Yanina Bar.

For more than two years the Bar family hid in the attic of their home, Jakob, Ita, and their three children—Joe, Jenny, and Marion—Riesenbach. They fed them, cared for them, and protected them, saving them from the certain death that falling into Nazi hands and being deported would have meant.

My family’s closeness to this story is direct: Ita was my grandfather Samuel’s cousin, and the two of them kept up a correspondence in Yiddish after the war, when the Riesenbachs were in a Displaced Persons (DP) camp, before emigrating to Canada. I still keep those letters.

For that heroic action, Józef, Julia, and Yanina Bar were recognized as Righteous Among the Nations.

In the late 1990s there was a reunion between the Anmuth and Riesenbach families, which culminated in September 2000 when we returned together to Markowa. There, Joe—one of those saved—met again with Yanina—one of the rescuers—55 years later. We had the privilege of witnessing that unforgettable embrace.

There were seven more families who managed to save lives. And there is also the tragic story of the Ulma family, who were hiding the Goldman family: they were betrayed, their house was raided, and all were murdered—the father, a pregnant mother, six children, and the Jewish family they were protecting.

Today in Markowa there is a very interesting museum that honors the memory of the Ulma family and also makes visible the other eight rescuing families. There, of course, is the recognition of the Bars, the saviors of our cousins from Canada.

When the museum was inaugurated in 2016 we were invited, although we could not attend. Even so, I stayed in touch with them and even collaborated by sending some photos of my grandfather. Now the time had come to visit the museum, where we were warmly and graciously received.

The museum’s director, Anna, was waiting to guide us together with María, a representative of the “Markowa Lovers” society. In addition, a grandson and great-grandson of Yanina Bar accompanied us throughout the visit to the museum.

I had the chance to meet Wasek Bar, Yanina’s grandson, back in 2000. I never imagined the welcome we would receive on our “return” to Markowa.

It was moving. The museum even has a reconstructed house with an attic where Jewish families hid. We climbed up, sat down, and shared reflections.

Despite the 36-degree heat and the cramped space in the attic under its low roof, I felt freshness and room. I felt very free.

The director then invited us for tea and a conversation about the museum. She asked me for educational suggestions based on my experience, which honored me deeply.

Illustration 3: Ulma Family Museum, Markowa

Illustration 4: Museum exterior wall. Names of the Bar family

Illustration 5: Typical Markowa house 80 years ago

Illustration 6: Vasek and Mikaw Bar, great‑grandson and great‑great‑grandson of Józef and Julia

Illustration 7: Markowa families who hid Jews during the Shoah

Illustration 8: Józef, Julia, and Yanina

Illustration 9: In a place like this, my five relatives were hidden for two years and five days

Illustration 10: Mariska of Markowa Lovers and Anna, Director of the Ulma Museum

Illustration 11: Kamil Kopera, museum researcher and author of the book on the Jews of Markowa

Later we went with Wasek and his son Mijaw to the Markowa cemetery, where we visited the graves of Józef, Julia, and Yanina Bar.

We also paid tribute to the Ulma family.

It was an indescribable emotion to stand before the graves of some of the kindest and most humane people in the world. We lit a candle and simply said Dziękuję (thank you).

We had met Yanina in 2000, in that unforgettable embrace with Joe Riesenbach.

And right there we received a message from Rosario: Maya Anmuth had been born, the first daughter of my niece and nephew, Jonatan and Romina, granddaughter of my brother Alejandro, pioneer of the new generation. Maya is the first great-great-granddaughter of my grandfather Samuel. The story of the Anmuths, from Markowa, continues vigorously in Rosario.

Coincidence or causality? I don’t know.

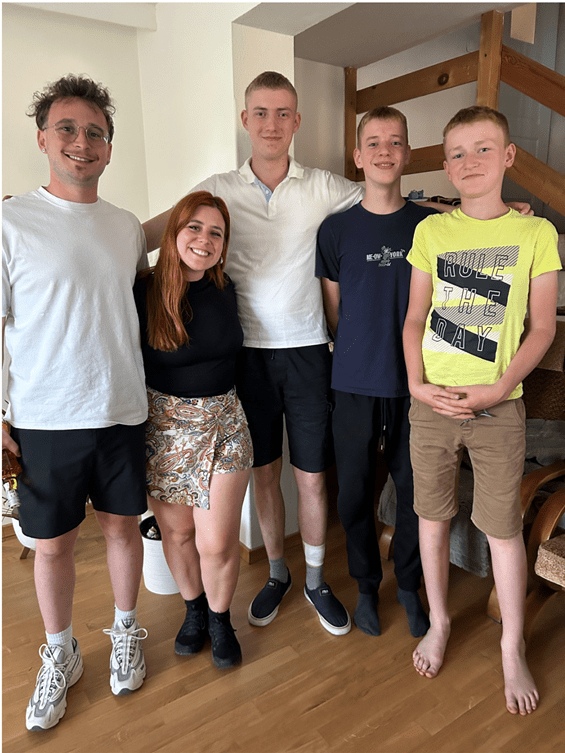

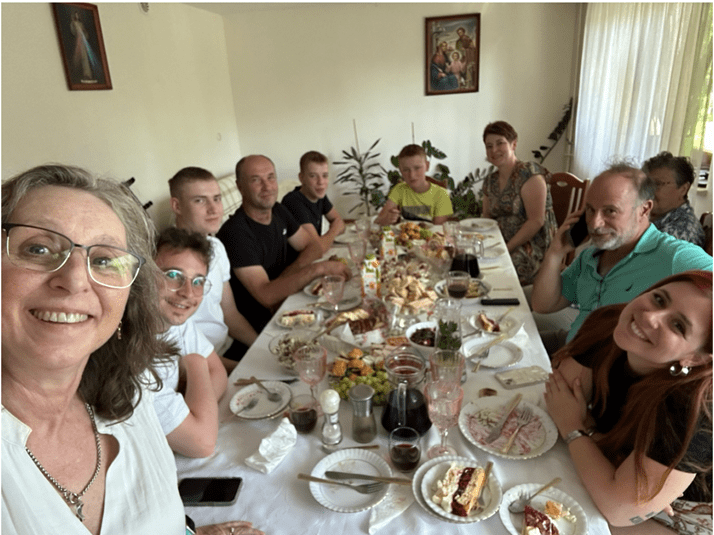

That afternoon we went to Wasek’s house. He, his wife Ela, their three children, and his mother Maria (Yanina Bar’s daughter) were waiting for us. The table was full of homemade foods, typical Polish dishes, prepared with love. There were ten of us, but there was food for thirty.

The descendants of the rescuers treated us extraordinarily, thanking us for visiting them. We were the grateful ones—not for the food or the hospitality, but for the opportunity to embrace them, to tell them that their grandparents were heroes, for the chance to meet them and express our gratitude.

In Canada, Ron Riesenbach (Joe’s son) joined us at the table via WhatsApp. It was an unforgettable after‑dinner gathering: bonds blossomed in an atmosphere of brotherhood and shared emotion (with great help from Michał, who speaks very good English, and from today’s translation technology).

As ties grew, a chess match even emerged between Wasek and my son Ariel, both aficionados of the “science game.” The rest of us watched that great match from the stands, amid laughter, comments, and camaraderie.

The household cats were also a reason to connect; there was a ride on a 20‑year‑old restored motorcycle, an exchange of gifts, and strong hugs accompanied by tears of emotion—the kind of things no translator can precisely convey.

Illustration 12: Some descendants of Józef, Julia, and Yanina

Illustration 13: With Maria, daughter of Yanina Bar

Illustration 14: At the home of Vasek and Ela, Markowa

Rzeszów

Upon our return to Rzeszów we met with Kamil Kopera, who led the research for the Markowa museum and with whom I have been in contact since 2016. He offered to guide us through Jewish Rzeszów.

It is important to note that many Jews from the Łańcut area were confined in the Rzeszów ghetto from 1941 until its liquidation in August 1942. We also toured the two synagogues in Rzeszów that still stand. Today, the municipality uses these buildings as a cultural center and a library.

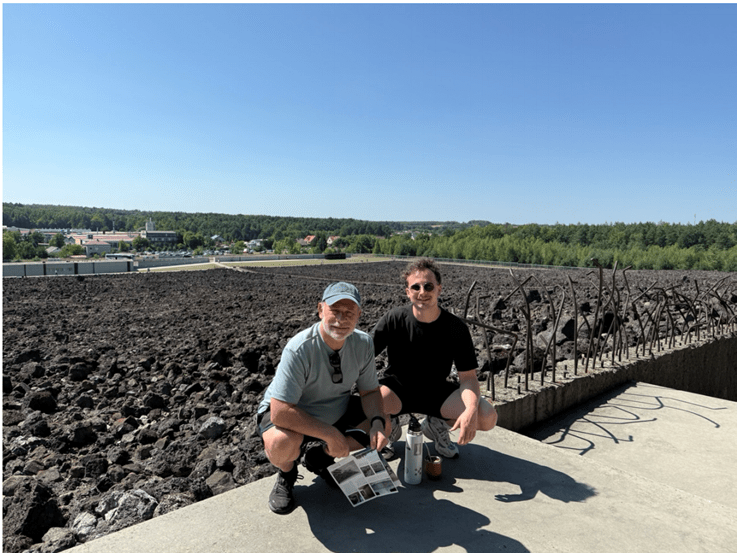

Bełżec – The Thunderous Silence

The next day we went to Bełżec, the extermination camp to which the Jews of Rzeszów and Łańcut were deported between August and November 1942.

The drive takes about two hours along rural roads in Subcarpathia, passing through small villages and towns that were once the scenes of vibrant Jewish life: synagogues filled with study and prayer, markets animated by Jewish merchants, cemeteries where memory was honored across generations, families who transmitted traditions and knowledge in every home. That effervescence, woven over centuries, was swept away in a few years by the Nazi machinery. Today, as you pass through those same towns, what you see are the traces of absence: synagogues in ruins, forgotten cemeteries, and spaces that seem silent but hold in their foundations the memory of the Jewish life that once flourished there.

Before the trip I had contacted Ewa Coper, the museum’s director. Since she would not be present, she left books on Operation Reinhardt and materials prepared for our visit.

The Bełżec memorial is overwhelming: an immense space—more than two hectares—marked by a thunderous silence. With every step you feel oppression, confinement, and absence.

Guiding my family there was a moment that will remain engraved forever. For a moment we shared the space with a group of Jews from the U.S., and together we recited, with tears, El Male Rachamim and the Kaddish.

Illustration 15: Bełżec extermination camp

Łańcut – The Synagogue and an Unexpected Discovery

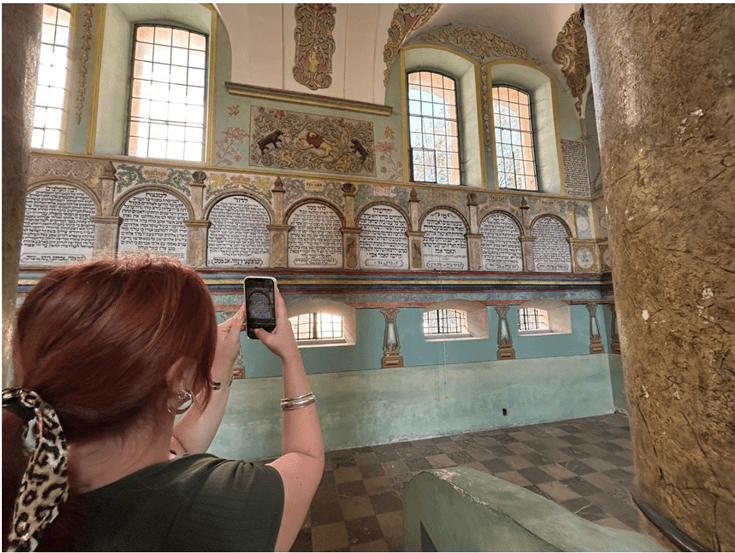

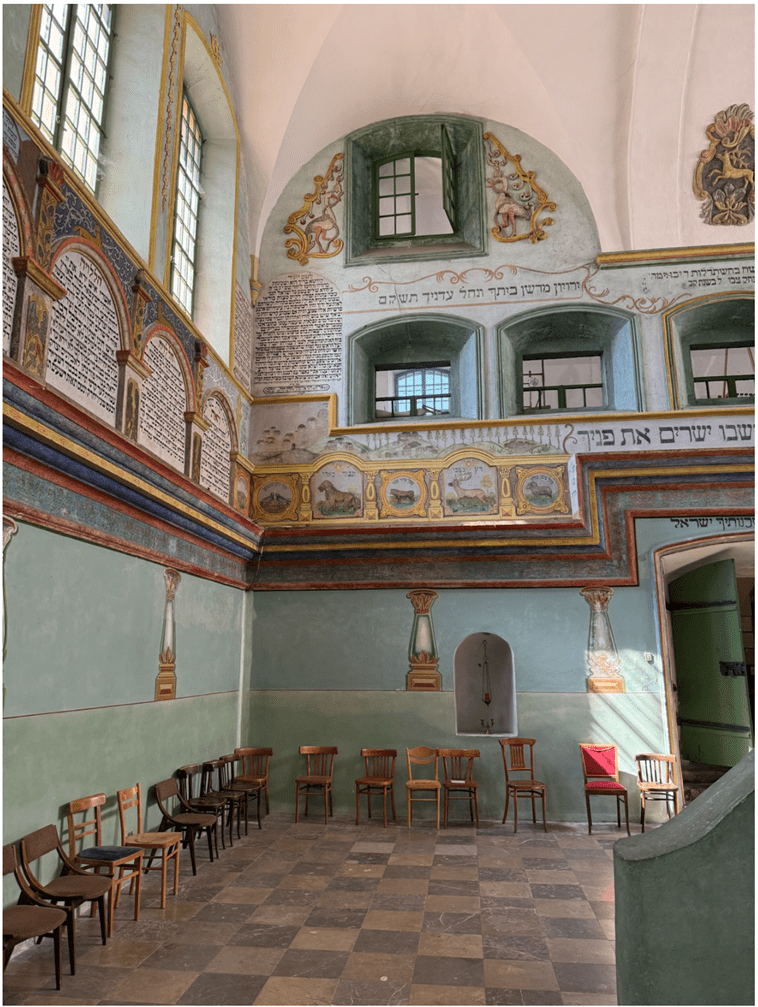

On the third day we visited the synagogue of Łańcut, preserved because the Nazis did not destroy it. I contacted Mirek, its caretaker. I was surprised that he preferred to speak in Hebrew: he had learned it on his own.

Astonished by his fluency, I asked him directly:

—“Mirek, are you Jewish?”

He smiled tenderly and replied:

—“I’m not Jewish. You understand—nobody’s perfect.”

We laughed with a mix of emotion, surprise, and complicity.

In our conversation, Mirek mentioned that the Anmuths had been linked to the synagogue. I, puzzled, immediately thought he meant recent donations for the restoration of the building, which was in very poor condition after the war.

But Mirek shook his head, smiled, and said calmly:

—“No, that’s not it…”

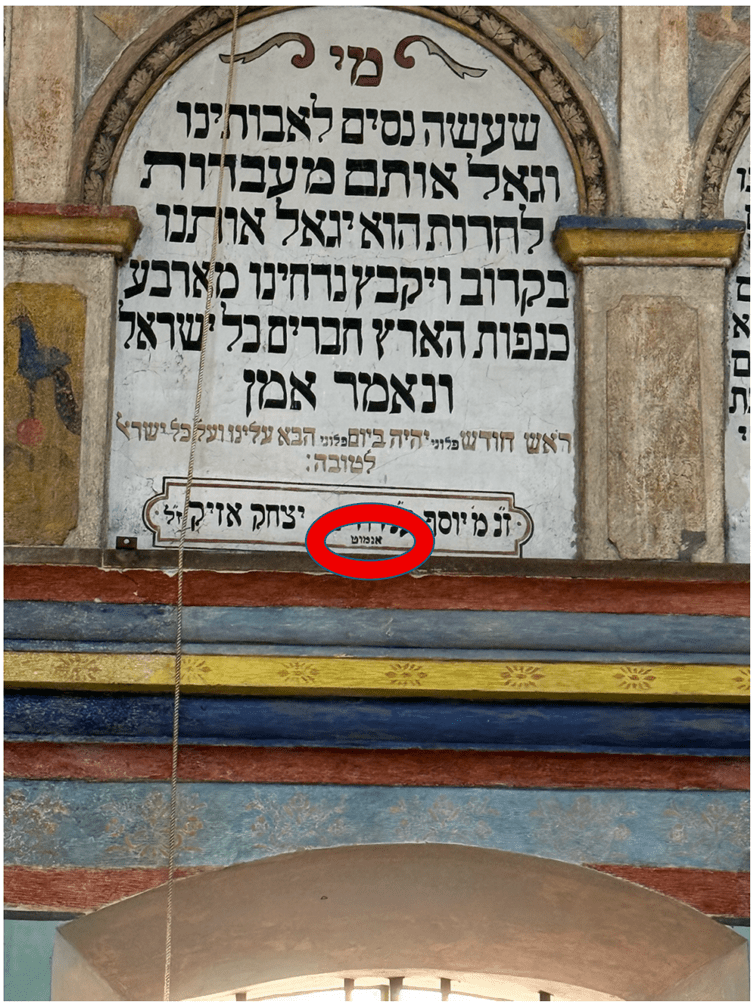

He then opened the door to the main hall and led us to the walls covered with 18th‑century frescoes. He pointed out two Hebrew inscriptions—blessings accompanied by family names—and at the bottom of both the surname appeared clearly: Anmuth.

I stood still, unable to believe what I was seeing. It was not a modern contribution, but the trace of my ancestors among the original donors to the construction of the synagogue in 1761.

The story came full circle in an unexpected way: our family had been present from the very origin of the Łańcut synagogue.

Illustration 16: Łańcut Synagogue, 1761

Illustration 17: Here the surname Anmuth appears written in Hebrew

Rzeszów and the Głowno Forest

Many Jews of Markowa and Łańcut were confined in the Rzeszów ghetto in 1941. Until then, the city had had a dynamic Jewish community, with active synagogues, schools, markets, and a cultural life that set the rhythm of daily existence.

In August 1942 the liquidation of the ghetto began: thousands were deported to Bełżec. The elderly and the sick who could not be transported were taken to the Głowno forest, about 7 km away, where they were murdered and buried in mass graves. There were more killings in that forest during the emptying of the ghetto.

Today, to reach the memorial, you walk about 15 minutes along a path surrounded by a beautiful, peaceful, and silent forest. In front of the graves we lit a Yizkor candle.

One of my sons asked me:

—“Were these trees witnesses?”

—“Yes,” I replied. “Silent witnesses, like so many humans were as well.”

We sat there, next to the memorial, and my children asked me for stories about my grandparents. In that place, among the trees, they came alive again, connecting with their great‑grandchildren. The millennial continuity of our people became present there. Right there.

Illustration 18: Głowno Forest

Illustration 19: Mass grave in the Głowno forest

That is why we returned to Poland.

Poland 2025

by Tami Anmuth, July 2025

Translated into English and adapted by Ron Riesenbach, August, 2025

I wanted European citizenship.

I wanted a red passport.

I just wanted that privilege.

I never believed that after six years of paperwork, searching, and phone calls that passport would finally arrive. But what I least imagined was what I would discover once I had it. It wasn’t just a red passport. It was a Polish passport, and so in 2025 I arrived in Poland—the country of my great‑grandparents—as a Pole.

It no longer felt so foreign; it wasn’t just the grand dream of a European document. It was right there. In Poland. As a Polish citizen.

In Poland I not only re‑encountered my roots, my family, my past. I also found myself—and my future.

In Warsaw I met up with my clan. Mom and Dad were coming from Bahia, Ari from Madrid, and I from London—really from Rosario. And we met.

My family. In Poland. As Poles.

My first impression was that the country was much more beautiful than in my memories from 2011, which were only cold, sadness, and grays—so many grays.

Now I saw warmth, I saw green, I saw sun, I saw color. And not just outside.

We arrived at the museum dedicated to the family with six children who were murdered for hiding Jews. That alone was a powerful symbol, wasn’t it?

A guide was waiting for us there. I thought it would be just another tour—another Shoah museum, another historical walkthrough to add to the long list of times I’ve been told dates, wars, numbers, and names that I retain for only a short period of time.

In part, it was that. The museum was that—but not entirely.

The guide arrived; we were still in the parking lot. I was sipping mate, getting ready to get out of the car and start the tour.

The guide came up and greeted my dad with a warm hug. Dad knows a lot of people in Shoah circles; it wasn’t that surprising.

It was Wasek—or however it’s spelled. Who’s that?

The son… whose son? I can’t understand anything. He’s speaking Polish; he doesn’t know English. Whose grandson? Yanina’s? Yanina—the one with the buckets of excrement? The one who lowered them from the attic where the Jews were hidden? The one who hid my family from the Nazis? Her?!

This very tall, big, blond, uncomplicated man—with a face more Polish than a pierogi —is basically a descendant of the rescuers? The ones we came to see and thank? He was. And he had come with his son.

Everything felt so strange at first. A stranger, in a parking lot, on an ordinary Tuesday at 11 a.m., with whom we didn’t share a single language in common.

We shook hands. We introduced ourselves. Luckily his 18‑year‑old son spoke English and helped the communication flow a little more. Still, it flowed only a little—not just because of language, but because we didn’t know what to say. Dad led the conversation; we talked about our jobs and occupations, the plane trip, and Michael’s (or however it’s spelled) plans for after finishing school.

The real guide arrived and took us into the museum.

At first glance, just another museum—nothing particularly special. They asked if, before the tour, we could go to another room. Sure, why not—it’s your museum, do what you want.

There was a table set with tea, coffee, and cake—and about five people waiting for us. Yes, waiting for us!

“Why are we so famous?” my brother asked. “No idea—because we’re Jewish?”

Do they want to make amends with cake and coffee for what Poles did to my people in the Second World War? Nah, stop it, Tami—don’t be so dramatic.

We were “famous” for being Jews who had returned to Markowa, where so many Jews—our family included—were murdered by the Nazis.

There were photos of my ancestors in that museum, and photos of the rescuers too—Wasek’s grandparents—right there beside me. What is all this? Everything felt so strange. I couldn’t decide what to feel.

They asked my dad questions; they even took notes and recorded him! Suddenly we were part of a documentary. There were people from the museum, people from the town of Markowa, historians—and everyone seemed extremely interested in what Dad had to say. They even asked us to come back and “please have some cake” before leaving, and once again recorded feedback about the museum. All very strange. While Dad spoke, I looked at Wasek and his son. A few generations after the rescuers. And me there, a few generations after the saved. They were silent, listening.

The kid looked bored—and sure, he’s 18. I’m 32 and I’m a little bored too.

They had life‑size replicas of the houses in which Poles lived—and life‑size replicas of the attic where Jews hid.

It was so small. We all climbed up: the museum’s informal fan club for our family, my family, and Wasek and Michał.

It was sweltering up there, and it smelled—and this was a replica, and twenty centimeters taller than the real one. And there we all were, sitting. Everything was so strange. My heart was racing, as if I were afraid to be there. Afraid of what? I never slept in a place like this for two years and five days, as my family did. There was something—a fiber inside me, a genetic transmission of that experience—pulsing. It was no longer “just another museum.” In that place, even though built for educational purposes, I felt things; I felt nervous; I felt afraid. How strange to feel a feeling that isn’t mine, that comes from other souls, isn’t it? Am I crazy? Yes, that too—but not because of this.

We finished the tour, the interview, the monologue. We took photos, they gave us books, and we left the museum.

It was four in the afternoon. We were starving.

Wasek invited us to eat at his house. Let’s remember: we’d met two hours earlier in the parking lot, right?

We stopped by the cemetery. We paid our respects. We lit candles. We honored—his grandmother, his great‑grandparents—the rescuers.

How can I be shaken by a photo, on a grave, with a cross, of a person I never saw or knew?

Maybe that emotion isn’t mine. But I’m honored to hold it.

We went to his house for lunch (even for the Anmuths, 4 p.m. was late for lunch). We assumed that, on an ordinary Tuesday, they’d already eaten.

After a few minutes driving through the countryside, in a small, random town in the middle of nowhere in Poland called Markowa, we arrived at his house—also in the middle of fields. Surrounded by tractors and crops (is that corn? no idea), there it was.

We went in. The table was set as if they were expecting the kings from Far, Far Away. What is all this? Why is there so much food, everything so beautifully prepared, sliced, and decorated—Pinterest‑level aesthetic? Is this for us? Were they expecting us? Why so much pampering? You’re the rescuers, you guys. Shouldn’t it be the other way round?

They welcomed us with love, hospitality, tenderness—and a level of warmth that overcame any language barrier.

At the house we were greeted by Ela, Wasek’s wife, who had made all of that homemade FOR US! (What?!) She was there with their two younger children. We shook hands, thanked them for the food, and apologized for being late. We sat down to eat.

Maria arrived—Wasek’s mother, Yanina’s daughter with the buckets, Julia and Józef’s daughter—the ones who decided to keep a Jewish family hidden in their attic for two years and five days, risking their own lives.

Little by little the mood shifted: from introductions to companions, to friends, to family. Yes— all in one day, in half a day—in a parking lot, a museum, a cemetery, and a farmhouse.

We were family.

We spent the afternoon with them—talked, ate until bursting, played with their kittens—and my dad even tried the middle brother’s motorcycle. They gave us chocolate, vodka (obviously), and a cushion.

I’ve just met them and I feel I love them. I don’t want to say goodbye. Good thing Mom forgot the envelope she had for them—that way we could return tomorrow.

Maria hugged us. Maria cried. Thanks to this woman’s grandparents, thousands more generations of Jews were saved—we’re at three and counting. She cried. I saw her cry and I cried too. What is this?

They thanked us for our gratitude. That’s it—Ari is right. They were grateful that we were there.

I had never seen such goodness.

I had never known a heart so big.

Do they realize who they are? The gold of a human heart that runs through their blood?

I wouldn’t have done it. I wouldn’t have risked my life and my family’s to hide a persecuted family. Even if I agreed they should be saved, my heart isn’t big enough to endanger my own for the morality and ethics of saving someone who doesn’t deserve to die. My heart isn’t that big.

Theirs was. Theirs is. I can see it today in their eyes—in the eyes of those three children I don’t know yet feel I want to protect.

We don’t know each other, and yet we’ve known each other our whole lives, across all lives, across all souls.

We went back to Wasek’s the next day.

We gave them the envelope from Ron, Joe’s son—the one who spent two years and five days in the attic—for Wasek, Maria’s son, Yanina’s grandson. The one who lowered the buckets of pee and poop from the hidden family for two years and five days.

Wasek was moved; he tried to hide it, and in his blue eyes I saw the gaze of humanity.

This time it was different—not because of the food (which, of course, once again covered the table as if we were at a five‑course dining experience in a Palermo restaurant), but because of the mood.

We were no longer getting to know each other. We were family. We ate, we chatted, Ari beat Wasek at chess.

I showed Ela photos of my little animals.

It was a family day. It felt so normal, so everyday, so natural.

I cried when we said goodbye—with real pain. I’ve just met you, but I’m going to miss you so much. I hope we meet again. This time we didn’t shake hands.

We gave each other a long hug.

We visited tourist towns that had witnessed the worst. Today they are beautiful places; a few decades ago, places of horror.

We listened to stories, saw places, walked on soil of war.

We went to a mass grave and lit candles. There was nothing but forest around us. How many of these trees must have seen death? What has this land heard? Down here lie my generations. Here I stand—Jewish, free, Argentine.

You there, buried—Jewish, imprisoned, murdered, Polish.

Both of us Anmuths.

I saw my surname in the ruins of a Shul; they were an active part of the community. A kind man showed us my surname written in Hebrew on the shul wall. Where are those Anmuths? Buried there? In some distant camp? Did anyone ever bury them at all?

Here I am, looking at ruins, learning history, asking myself these questions… And afterwards I’m going to have a beer with my family.

We went to an extermination camp—Bełżec, or however it’s spelled.

Pain was in the air. I could feel it—the despair, the disillusionment.

In this gas chamber I’m now standing in, my ancestors died. In this gas chamber—where I’m now singing Hatikvah with strangers—my relatives screamed in desperation.

I find my name among the victims’ names: Tamara.

I silently send a greeting to the soul of my namesake—wherever she is—wishing, fooling myself with the possibility, that her death was quick and painless. Here, in this gas chamber where today I, Tamara, am standing in new sneakers, drinking mate, wearing SPF‑50 sunscreen, I send love to that other Tamara—whose reality seems to have been a little different from mine.

There is sun, there is silence, there is calm.

I breathe pain. I feel it. Don’t you, Ari? No? Sometimes empathy is both a virtue and a curse.

We sang.

Mom cried. I hugged her. Mom accompanied me to the museum, where there is history, photos, texts—and a dark, cold, echoing space for “contemplation.” I contemplate. I contemplate Mom waiting for me to leave the museum and continue the journey. I contemplate my luck.

I sought Polish citizenship in search of a prestigious passport, and in that search I found something much, much better: I found meaning.

I found goodness, I found connection, I found love, I found family, I found solidarity.

And above all—before all: I found gratitude.

To those who were there.

To those who saved them.

To those who are here.

To us who are here.

To myself—who am here.

Jewish, free, Argentine—

And Polish.

Return to Riesenbach Family History